So…. one of the tropes that keeps coming around is that our voting system is broken, and that there is rampant fraud. Often this is stated in terms of supposed “illegal” people voting – and of course “stealing” our healthcare, blah blah blah.

Here are some facts about this – and I encourage readers to become #factivists as much as possible. Exercise your critical thinking! Question your sources of information! Be free!!

- The Brennan Center for Justice’s 2024 review of so-called voter fraud. In their review and subsequent article entitled Debunking the Voter Fraud Myth, this quote really stands out:

The report reviewed elections that had been meticulously studied for voter fraud, and found incident rates between 0.0003 percent and 0.0025 percent. Given this tiny incident rate for voter impersonation fraud, it is more likely, the report noted, that an American “will be struck by lightning than that he will impersonate another voter at the polls.”

2. Non-legal residents are simply not allowed to vote in state and federal elections. This is not new. Repeating. THIS IS NOT NEW. When we vote we are challenged to present our credentials AND check a box that we can be pursued legally if we misrepresent any information about our voting status. Oh. And one more point on this. The undocumented people I am friends with WOULD NEVER TRY to vote. They know! They do not want to endanger their own livelihoods, households, kids in college, dreams of citizenship, by posing as legal voters.

3. More than SIXTY lawsuits that Trump and his followers launched following the 2020 election revealed NO substantive voting fraud issues – across numerous states. SIXTY. Many of those processes were overseen by REPUBLICAN-APPOINTED judges!

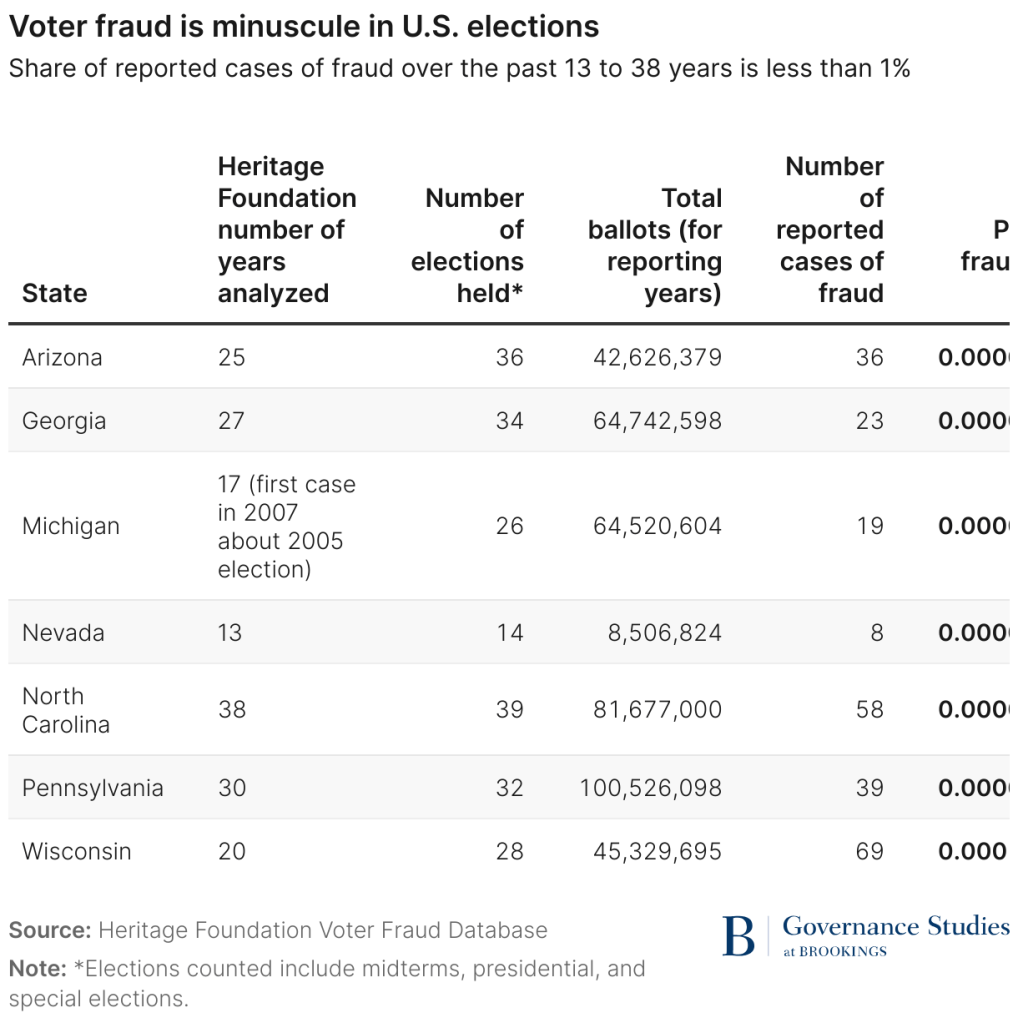

4. The Heritage Foundation’s own work (omg please. I hope I never quote them again). The Brookings Institute did a review of the Heritage Foundation’s tracking of supposed voter fraud in the U.S. The following tells the whole story – that they had to go back more than 30 (THIRTY) years looking at all state and federal elections to come up with a number that people are now using in their arguments.

My own state of North Carolina, over THIRTY EIGHT years, with more than 81 MILLION votes cast, reported a total of 58 instances of voter fraud. That’s it.

So.

When this bag-of-wind president and his boot-licking followers pound the podium for supposed ‘voting integrity’ take a step back and ask them and yourself what this is REALLY about. This is REALLY about imposing unnecessary roadblocks for folks to vote. That’s all.

When you can’t win by playing fairly by the agreed rules, you impose new and unnecessary rules that benefit your side.